|

**This piece of writing contains images of persons who have since passed on to the spirit world

RADIOACTIVE EXPOSURE TOUR === In

September 2013, I found myself sitting in an apartment

across the street from Nagano Park in Osaka. There was a

ceaseless mechanical whirr of cicadas in the background and

a sheath of fine sweat over my body as summer blared on. I

was out of money and ready to start living off of my line of

credit. I was deciding whether to return home to Canada or

go back to Melbourne where my heart strings were tugging me

towards.  In

December, I ended up at a Mad Max-themed fundraiser

at a warehouse in Brunswick. To get there, I walked from the

tram and down a side street, then through a portal-esque

laneway and then turned down another laneway where people

were gathered in little pods and draped along the pavement

smoking, drinking and chatting. I found my pod inside and we

sat on the floor watching one of the opening acts, an upbeat

folk-punk band called the Glitter Rats. People were walking

around wearing elaborate homemade Mad Max-themed

outfits with mohawks and smears of black eyeliner. Artwork

and posters covered the walls and there were several mini

bars. On the upper floor, where I found the cramped solitary

bathroom, were enclaves where people lived. Everything was

warm, wooden and electrifying.  The

Radioactive Exposure Tour was put together to educate

people first hand about the nuclear industry and has been

running for over 30 years. The 2014 tour was one of the

most ambitious to date and was organized by the Friends of

the Earth, the ACE Collective – an anti-nuclear group- and

former participants who volunteered their time.  The first thing that had struck me about Melbourne when I arrived there was how giant and expansive the skies were. Coming from British Columbia, most of which is closed in by mountains, it felt really freeing. And the weather in Melbourne was quite unique, with warm northern desert winds mixing and colliding with icy southern winds, creating an ever shifting skyscape and extreme weather fluctuations. I fell completely in love with Melbourne and the surrounding areas and throughout the course of my interspersed time in Australia, I hadn’t left to explore any other provinces: I was going to make up for that big time. Our

convoy all met up in Beaufort and then we continued West

of Melbourne past Mount Zero and some picturesque

rolling hills. Then we went through the Grampions, Nhil

and the entrance to Desert Park. Every once in a while,

a grey Wallaby would hop by in the distance or turn and

look at us.  My

decision to come to Australia was somewhat reckless. I

was pretty messed up from some personal traumas I had

been through and I found the Pacific Northwest winters

hard to take. There was a seat sale to Melbourne and I

wanted to cheat the nature godds and get two summers

in one year. I imagined myself on a pale sandy beach,

sipping lemon sodas and meeting cute boys as my PTSD

and seasonal depression melted away under a Southern

sun.  We

made it all the way to Adelaide on that first day,

despite the big bus breaking down. We got it back up

and running and arrived in the evening at a large

country home on the outskirts of town where we had a

big fire and ate a delicious dinner provided by Food

Not Bombs.  On a side note, in 2009, in an incredible act of hypocrisy, Peter Garret, lead singer of Midnight Oil, who in the 1980’s sang a song called 'Beds Are Burning' - a passionate plea for Aboriginal Rights - approved the expansion of the Beverly Mine and the opening of a new uranium mine in Southern Australia during his role as the Environment Minister after moving from music into politics.

From Port Augusta we headed to Woomera, a town

with a population of 146, where the Australian

and British governments carried out atomic

testing in the 1950’s and 60’s. A former

government employee turned whistleblower called

Avon

Hudson joined in on the tour and took us

to our camp on the outskirts of town.

The town exists solely for the purpose of

housing employees of the Olympic Dam mine run

by BHP Billiton, which is one of the largest

uranium mines in the world. We went on an

official tour, asked some questions and took

some photos. Huge amounts of water are used in

the processing of uranium and the material is

highly toxic and radioactive, so extreme care

needs to be taken during the entire extraction

and transportation process. The by-products of

producing energy with uranium include

plutonium, which is used in the manufacturing

of atomic weapons, the most destructive force

on planet earth. During the whole nuclear

cycle, different levels of nuclear waste are

are created, some of which is hazardous for

hundreds of thousands of years.

After visiting the mine, we travelled to

Lake Eyre. The sun was falling into the

horizon and as we arrived the sky turned

neon orange and the moon was eclipsed by the

setting sun.

The days were starting to bleed together

and the next morning we packed up all the

cooking and camping gear and packed

ourselves back into various vehicles to

make our way to Mound Springs. I ended up

moving from the SUV on to the big 'Road

Warrior' bus.

After Mound Springs, we were all lost in

our own thoughts as we drove deeper into

the desert lands. The ‘big wet’, which

spilled out 2/3 of the annual rainfall

for the region in a week, resulted in

the cropping up of little lakes all

around. Birds flocked to the water, the

sun glinted off of the fresh electric

green brush and vibrant little red,

yellow, orange, pink and purple desert

flowers were coaxed out of their dormant

shells. It was ridiculously beautiful.  The next day we headed to Coober Pedy and I hung out with Fran and Jarrod from the Glitter Rats and their two young twin boys. There were so many awesome and interesting people on the tour and day-by-day I was getting to know more of them.

I ended up jumping into a different

truck with Fran and Jarrod and we

headed to our next destination,

Walatinna Station, to visit Yami

Lester, a Yankuntjatjarra elder who

had been blinded by the atomic tests

that were done in the 1950’s. As we

drove out from Coober Pedy, the

terrain morphed from bare pockmarked

sandstone to an expanse of flat,

pale sand with low brush and small

rocks. More bright desert

wildflowers were bursting out from

the pastel backdrop. After about an

hour, we officially entered the

Northern Territory.

The sun had fallen and the horizon

was humming with reds, oranges,

soft pinks, blues, and purples and

a few illuminated clouds sparkled

through the trees. On every other

night the falling sun had been

quickly followed by the rising

moon, though that night the hills

and trees kept the moon at bay for

a couple of hours and we were able

to see the unhindered beauty of

the starry sky. Mars was out and

the band of the milky way streaked

over our heads like a fireworks

tail. I laid down on one of the

open areas of the property staring

up at the sky until the moon crept

over the trees.

The next day we all hung out

with Yami, who had a generous

spirit and a giant smile. He

told us the story of how he had

been blinded by the nuclear

fallout from the testing that

had taken place. It was 1953 and

he was living in the bush near

Maralinga with his family. None

of them were notified of the

testing.

--

It was dark when we arrived

and we were greeted by Barbara

Shaw, an ardent

anti-Interventionist and

Aboriginal rights activist,

who I recognized from John

Pilger’s film 'Utopia' and

the Our Generation

documentary. Barb has

ancestral ties to Muckaty

through her grandmother and

lived in one of the

ghettoized areas of Alice

Springs called a "Town

Camp". Some of what Barb

said when she welcomed us

was:

I decided to walk from the

camp along the Todd river

and spend the day

wandering around Alice

Springs alone. When I

mentioned it to some of

the girls who were on the

bus with me as I was

getting ready to leave,

they told me that I

shouldn't go alone because

I might "get raped". I

left the bus and found one

of the locals and

long-time activists and

asked her if it would be

safe. She said that it

wouldn't be a problem at

all and I would just see

"drunk people hanging out

around the river". When I

returned to the bus, I

brought up the comment the

girls had made previously

and they denied having

said it and said that that

it wasn't what they meant.

I left the bus and headed

through the outskirts of

the city and made my way

to the public pool. I was

ready for a hot shower.

As I continued my

exploration of the town

on foot, seeing the

Third World living

conditions in many areas

was really upsetting and

there was continual

harassment of

Aboriginals by local

police. In the evening,

we all gathered at the

Totem Theatre to hear

from people affected by

the Intervention and

learn more about the

Muckaty campaign.

Part of the

Intervention also

involved the

discontinuation of

funding for many

remote ‘homelands’ and

the moving of people

into hub communities

controlled by White

Australians. The

homelands were places

where people practiced

traditional hunting

and ceremony and many

found a lot of healing

there, so it was

devastating for a lot

of people to be moved

away. In the end, the

Intervention ended up

worsening all of the

social conditions that

the program was

supposedly trying to

address.

The next day we had

the option of

participating in a

demonstration at

Pine Gap, a

satellite tracking

station jointly run

by the American and

Australian

governments, which

many consider puts

Australia at risk in

the event of global

nuclear tensions. I

ended up staying in

town and spent most

of the day hanging

out around the camp.

I wasn’t ready to do

full-on direct

action, though I

admired those who

were.

‘Uncle Kev’, whose

traditional

territory is

around Lake Eyre,

has been involved

in anti-nuclear

and Aboriginal

rights actions for

over 40 years

including sit-ins,

peace walks,

government

eviction notices

and participation

in the Aboriginal

Tent Embassy in

Canberra. He

reclaimed the emu

and kangaroo from

the Autralian coat

of arms, charged

the government

with genocide and

traveled to Europe

in 2001 after

winnning the

Nuclear-Free

Future Award. He’s

been called a

“jedi of the

anti-nuclear

movement”.

The next day we

drove from Alice

Springs to

Tenant Creek.

Ridges and hills

disappeared into

dense brush, gum

trees and light

sandy expanses

with

stalagtite-esque

ant hills

protruding like

bizarre polyps.

It was a long

drive and we

stopped along

the way and had

a swim in a

little lake.

When we

arrived in

Tenant Creek

there were

some community

members (aka

“mob”) there

to meet us,

though a

member had

recently died

so a lot of

people stayed

home in

mourning

(“sorry

business”). We

all hung out

by a river,

had some

snacks and

then headed

out to the

outskirts of

town where

we’d be

sleeping. One

of the main

campaigners

against the

nuclear waste

dump, Diane

Stokes - a

Yapa Yapa

elder, brought

us to our

campsite and

welcomed us in

her

traditional

language. She

told us where

to light fires

for the

spirits and to

watch out for

little people

who roam

around in the

night. We set

up our gear in

the dark.

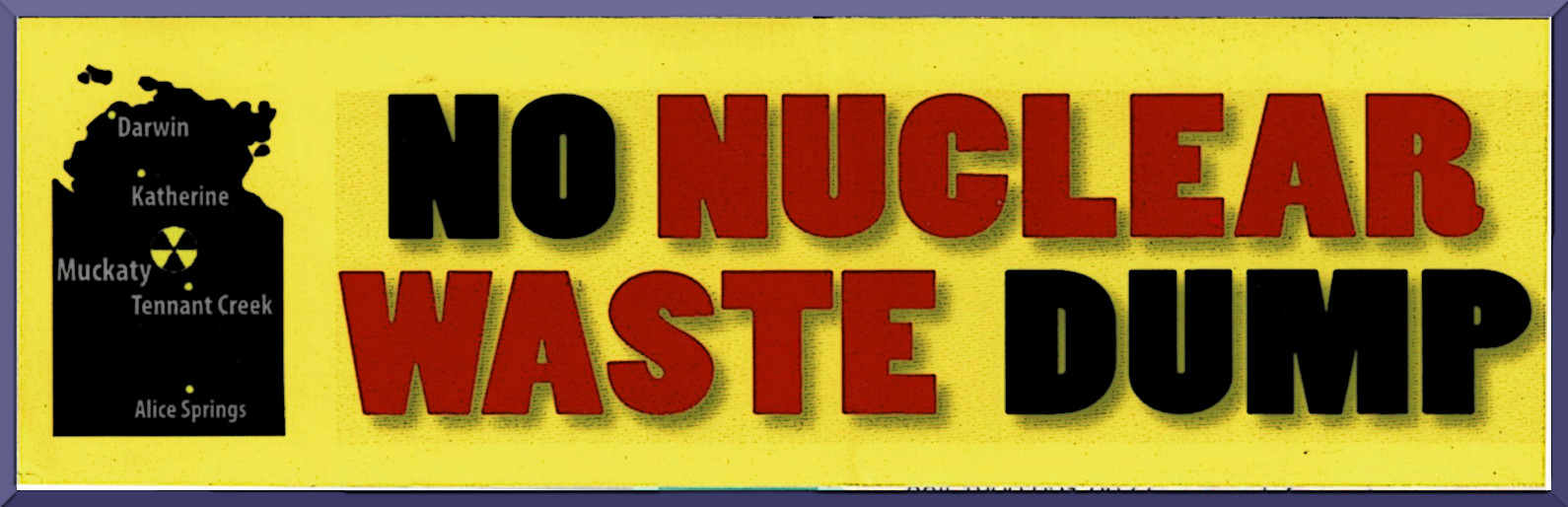

Paralleling

the

Intervention

program, which

relied on the

suspension of

the Racial

Discrimination

Act; both the

Environmental

Protection and

Biodiversity

Conservation

Act and the

Aboriginal and

Torres

Straight

Islander

Heritage

Protection Act

were suspended

during the

site selection

phase for the

nuclear waste

dump. As well,

details of the

agreement

between the

government and

the Northern

Land Council

were withheld

from the

public.

The Australian

government has

been looking

for a place to

put its

nuclear waste

since the

1950's and, as

Ferguson

stated in an

interview with

ABC News,

"It's time for

Australia to

front up to

it's

responsibilities.

It's a moral

issue. If you

want access to

nuclear

medicine, then

take

responsibility

for storing

your waste."

Yet according

to Nuclear

Radiologist

Dr. Peter

Karamoskos the

nuclear waste

had “nothing

to do with

nuclear

medicine" and

is being used

"to get the

public on side

through an

emotive

campaign of

disinformation."

Diane Stokes (center), Bunny (foreground)

To finish off

our Muckaty

experience,

more of “the

mob” came out

and spent time

with us,

including Kylie

Sambo. Two

fires were lit

and a large

group sat

around each

fire

representing

to different skin

systems - one

of the many

complex social

systems that

are part of

Aboriginal

culture. It

was nice to

get to hang

out with

everyone

again; we were

able to have

more

meaningful

interactions

and I got to

meet some of

the local

children. We

ended up

exploring the

surrounding

area and found

an abandoned

school bus to

hang out in.

We were all

hopping over

the seats and

running down

the aisles and

they told me

their real

names and that

they all spoke

3 different

local

languages.

When we headed

out of Muckaty

the next day

we stopped at

a cultural

centre in

Tenant Creek

and saw some

women making

artwork. I was

told that a

lot of the

distinctive

Aboriginal dot

paintings

represents an

aerial

perspective

and are the

visions people

see in the

Dreaming.

We stopped in

Alice Springs

again for the

night and

camped next to

the Town Camp

again. The

next day we

drove from

Alice Springs

to Coober

Pedy. I ended

up staying

with a German

woman who

lived in one

of the

dugouts. She

was friends

with one of

the other tour

participants,

a retired

woman who had

been part of a

previous

anti-nuclear

campaigns in

Southern

Australia and

who had worked

as a

missionary.

We continued

on and the

scenery

flashed by

like a dream.

There were

run-down

roadhouse

cafes, wild

camels and

large ruddy

kangaroos out

in the

distance.

There was a

lot of

roadkill along

the highway of

cattle, sheep

and kangaroos,

and I saw some

bizarre,

contorted,

wild horse

carcasses,

thrashed and

gnarled and

melting into

the sandy

desert floor.

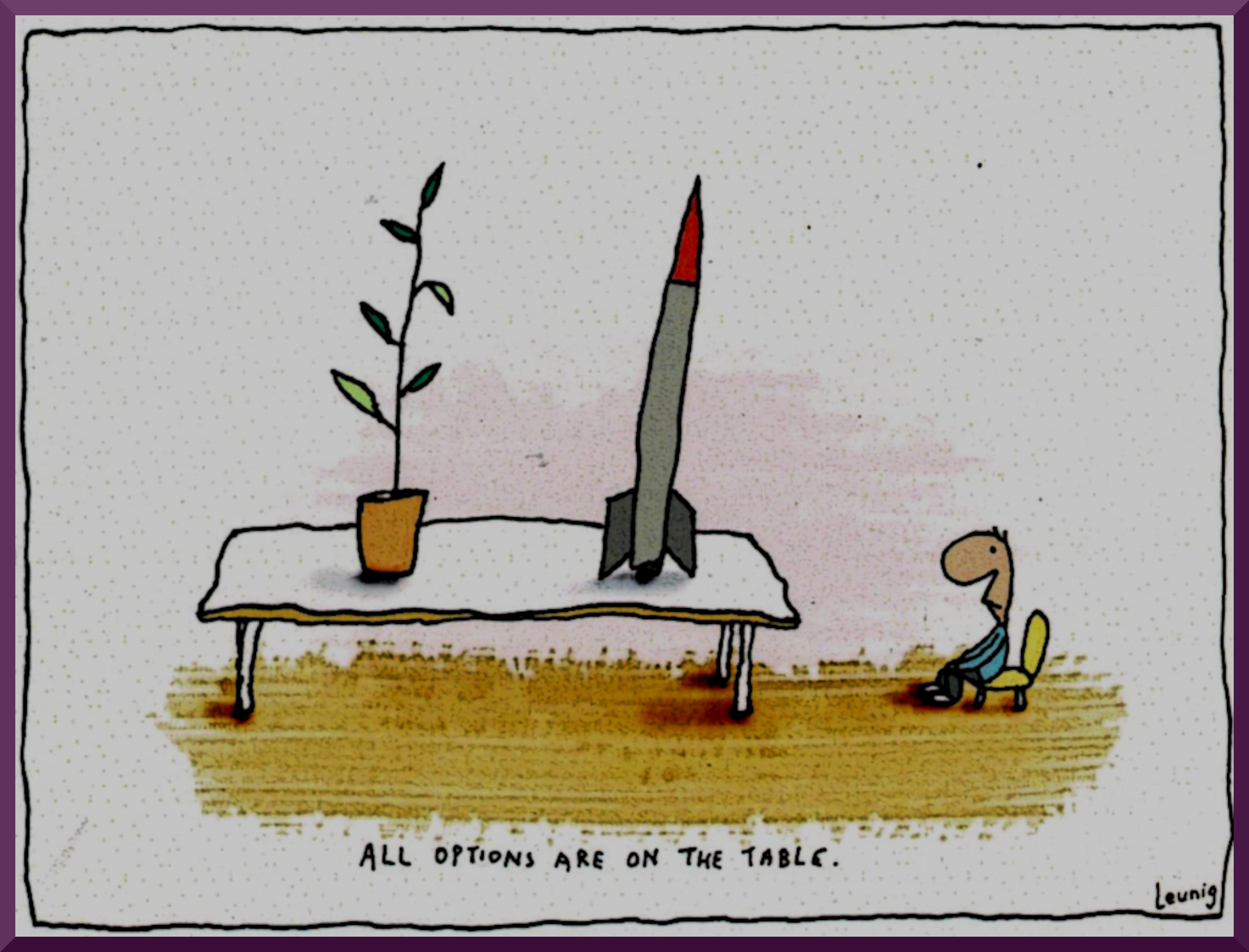

Many people

herald nuclear

energy as a

clean source

of energy and

the wave of

the future.

It’s hard for

me to see that

after

everything I

learned on the

RAD tour.

There are

extreme

hazards and

environmental

concerns from

the

astronomical

use of water

during the

initial mining

to the ongoing

dangers of

radioactive

waste. And the

continued

nuclear

armament of

nations

globally is

really scary.

We’ve seen

what horrible

destruction

nuclear

weapons cause

in Hiroshima

and Nagasaki

and the

devastation

caused by the

Chernobyl and

Fukushima

nuclear

meltdowns. I

remember

reading Keiji

Nakazawa’s Barefoot

Gen comic

about living

through

Hiroshima, and

it's hard to

fully absorb

the scale of

the

destruction

caused.

Shortly after

returning home

I discovered

that the

Muckaty

campaign had

been won,

which was so

great and I

know so many

people fought

so long and so

hard!

Unfortunately,

the fight

continues to

bring

awareness

about the

dangers of the

nuclear

industry,

prevent

nuclear

armament, stop

waste dumps

from being

imposed on

other

communities

and seek a

transition to

clean

alternatives

to nuclear

energy. And

the policies

of the

Intervention

have yet to be

fully

repealed. MORE ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIA / RAD TOUR INFORMATION:

Black

As INFORMATION ON THE NORTHERN TURTLE ISLAND / CANADIAN NUCLEAR INDUSTRY:

The

Committee For

Future

Generations

|

|

Widget

is loading comments...

|